President Donald Trump’s dogged determination to annex the icy island of Greenland relies on the idea that doing so would give the U.S. an untapped treasure trove of natural resources and strategic military positioning. But the harsh environment, enormous financial investments, and massive infrastructure and workforce buildout required to create an economic engine could cost at least $1 trillion over two decades and make little to no economic sense, according to industry and geopolitical analysts.

The prize is great on paper for a real estate tycoon like Trump—after all, Greenland would exceed the Louisiana Purchase as the largest geographic acquisition in U.S. history. But multiple specialists in the region and its resources dismiss the economic reasoning as nonsensical, given that Greenland already is open to greater U.S. investment and military scale-up.

Greenland may be home to large reserves of critical minerals and crude oil, but they’re much cheaper to extract elsewhere in the world, including within the Lower 48, said Otto Svendsen, associate fellow specializing in the Arctic for the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

“The business case is non-existent, setting aside all the political and legal and practical reasons for why I think it’s impossible,” Svendsen told Fortune.

The White House’s own estimations place the cost of a purchase of Greenland close to $700 billion, he said. Then there are the hundreds of billions of dollars needed to fund the developments of mines, oil drilling, roads, electrification, ports, and more—with a wait of 10 to 20 years before seeing any notable commercial success. The U.S. would also presumably assume Denmark’s roughly $700 million in annual subsidies in perpetuity to pay for the education, health care, and more of Greenland’s 56,000 residents.

“The numbers just don’t add up at all,” Svendsen said. “It cannot be hammered home enough that the U.S. has an incredibly favorable arrangement at the moment with an incredible amount of access to Greenlandic territory, both to advance its security and its economic interests.”

Despite ample efforts over the years to develop mines and drill for oil—the last, unsuccessful drilling bid was abandoned in 2011—Greenland today is home to zero oil production and just two active mines, neither of which extract the desired rare earths essential to computer, automotive, and military defense equipment. There’s a small gold mine and another for anorthosite—a mineral used to produce fiberglass, paint, and other common materials. While some rare earths and oil projects are in development—by U.S. companies—they remain in early stages, with no guarantees of success.

The relative lack of success over decades is no fluke, said Malte Humpert, senior fellow and founder of The Arctic Institute nonprofit think tank.

“You’re dealing with ice, polar bears, darkness, lack of power, the sea ice being frozen, really low temperatures. It’s probably one of the roughest places on Earth,” Humpert said. “The fact that it hasn’t been done—when it could have been done—is really all you need to know. It’s very difficult to make it economical.”

None of this has publicly deterred the president, nor has the risk of shattering international laws and the NATO alliance. The White House describes owning Greenland as a national security imperative—a rationale that might outweigh the poor economics of an annexation. But analysts say existing treaties give the U.S. all the needed military advantages in the Arctic with the potential to grow and negotiate for even more.

As Trump focuses on his new “Donroe” doctrine and forewarns of a blitz through much of the Western Hemisphere—since launching a military strike in Venezuela this month, he’s threatened Colombia, Cuba, and Mexico—he has set his sights on annexing Greenland by any means necessary, through a purchase or military action.

“We are going to do something on Greenland whether they like it or not,” Trump told reporters last week. “I would like to make a deal and do it the easy way. But, if we don’t make a deal, we’re going to do it the hard way.”

While Trump publicly mulls seizing Greenland by force, Secretary of State Marco Rubio has focused on a negotiated purchase, which is a type of international diplomacy not practiced since World War II, and an approach that Denmark and Greenland have repeatedly rejected. The White House did not immediately respond to a request for additional comment.

The Trump administration already is planning a large upgrade of its only military base in Greenland, the Pituffik Space Base, with the potential to expand much more.

So why not just continue to grow your existing U.S. footprint in Greenland? If the U.S. doesn’t annex Greenland, then Russia or China will instead, Trump has insisted. “When we own it, we defend it,” the former real estate developer said. “You don’t defend leases the same way. You have to own it.”

What’s at stake

After Trump initiated tariffs and trade wars last year, the United States’ over-reliance on China for critical minerals—especially rare earths—became painfully apparent when China threatened to withhold the necessary soft metals that drive America’s economy and help bolster its national security.

The oxymoron of rare earths is that they’re abundant around the world, but harder to find in larger concentrations that make the economics worthwhile. Greenland theoretically offers those large concentrations.

Greenland’s estimated rare earths reserves offer a smorgasbord of 1.5 million metric tons, including the more uncommon heavy rare earths. That would rank Greenland eighth worldwide, coincidentally just behind the United States, but well behind China and its 44 million tons, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

But as the research firm Wood Mackenzie says in a new report, “Here, ambition runs up against reality. Around 80% of the island is covered by the Greenland Ice Sheet, averaging a mile thick, meaning only limited work has been undertaken to quantify the true scale of Greenland’s deposits.”

An even bigger challenge is the higher costs of developing a mining industry in Greenland’s harsh terrain, where there’s little to no existing infrastructure. There are just a few short, warmer windows when drilling and mining are practical; there is less daylight than almost anywhere on earth; and most of the terrain is accessible only by helicopter.

But the less-discussed issue is that mining is only part of the equation, said Jennifer Li, senior geopolitical analyst for the Rystad Energy research firm.

In tandem, the U.S. must develop a much more extensive rare-earths processing and refining industry if it wants to break China’s near-global monopoly on the complicated refining process. That would mean constructing more minerals refineries in Greenland or elsewhere in the U.S. (Currently some domestic projects are underway, including ones with U.S. subsidies and direct government equity investments.)

The U.S. would also likely have to further subsidize the critical minerals sales with a floor pricing mechanism, to compete against China’s repeated price-dumping practices.

A race for resources

Greenland and Venezuela may represent very different cases, Li said, but they both come back to Trump’s focus on Western Hemisphere dominance and “governing from afar in order to try to change the policy regime.”

In Venezuela, the focus is on crude oil. In Greenland, it’s on critical minerals mining, including rare earths and uranium, and oil drilling. Greenland currently has moratoriums on both uranium mining and on oil drilling—minus grandfathered licenses that allowedone Texas company to drill for oil this summer. “There are a lot of ecological concerns,” Lisaid.

Trump could theoretically end those moratoriums and expedite permitting, essentially green-lighting Greenland for more mining and oil drilling.

Still, “even green-lighting rhetorically isn’t going to lead to seismic changes overnight,” Li said, given the historic lack of success in mining and oil drilling exploration and the many years of infrastructure construction required to build a commercial industry. A “more cooperative dialogue” with Greenland, Denmark, and NATO is a more feasible approach, Li said, than taking things further with annexation or military action.

Current tensions aside, Greenland is eager to attract much more U.S. investment, just not at the expense of ownership and sovereignty, said Christian Keldsen, managing director of the Greenland Business Association.

After all, 97% of Greenland’s exports are seafood, mostly shrimp. And Denmark’s subsidies account for over half of Greenland’s total revenues. Mining is only a tiny piece of the pie. Greenland wants the U.S. to invest in its mining and energy sectors, even developing data center campuses in the spacious and cold terrain that could prove suitable for such facilities, Keldsen said.

Just don’t conquer the icy and barren island. “We’re somewhat irritated by this. We’ve had an open business relationship with the U.S. for years,” Keldsen said. “All this talk creates instability and noise in the background. And, if there’s anything investors don’t like, it’s instability.”

What Trump wants

For all the focus on seizing Greenland of late, it was a cosmetics heir who first put the bug in Trump’s ear during his first term.

Back in 2018, during his first presidential term, Trump’s longtime friend, billionaire Ronald Lauder—from the family of Estée Lauder fame—discussed with Trump the importance of Greenland’s resources and strategic Arctic positioning, especially as ongoing global warming melts the ice sheets and creates more passageways between the U.S. and Russia. (Lauder declined comment for this story.)

Shortly thereafter, Australian geologist Greg Barnes, who founded the massive Tanbreez rare earths mining project in Greenland, which remains in development, briefed Trump at the White House. Last year, New York-based Critical Metals acquired 92.5% ownership of Tanbreez. A pilot project launched earlier in January, although full construction is yet to begin.

“In the 19th century, there was the gold boom. The 20th century was the oil boom,” Critical Metals CEO Tony Sage told Fortune in a recent interview. “We’re in the rare earths boom now, but this boom is going to fund everything for the next 30 to 50 years. Everything in your life needs rare earths.”

The rationale for acquiring Greenland may have less to do with the economic case, and more with Trump’s ego and his real estate background, said historians and analysts who are critical of the idea.

By a difference of just 8,000 square miles, an annexation of Greenland and its estimated 836,000 square miles would exceed the 1803 Louisiana Purchase and its 828,000 square miles, potentially making it the largest acquisition in U.S. history, noted David Silbey, a military historian at Cornell University.

“This is the biggest land grab ever. He loves big things, huge things, he would say,” Silbey said. “He’s a New York real estate guy. He likes to grab land, and he grew up in a world where bullying was part of business practice. He like to bully, and he’s picking on the little guy.”

Because Greenland doesn’t “move the needle economically in any way, shape, or form,” Trump following his real estate instincts is the most logical answer, Silbey said.

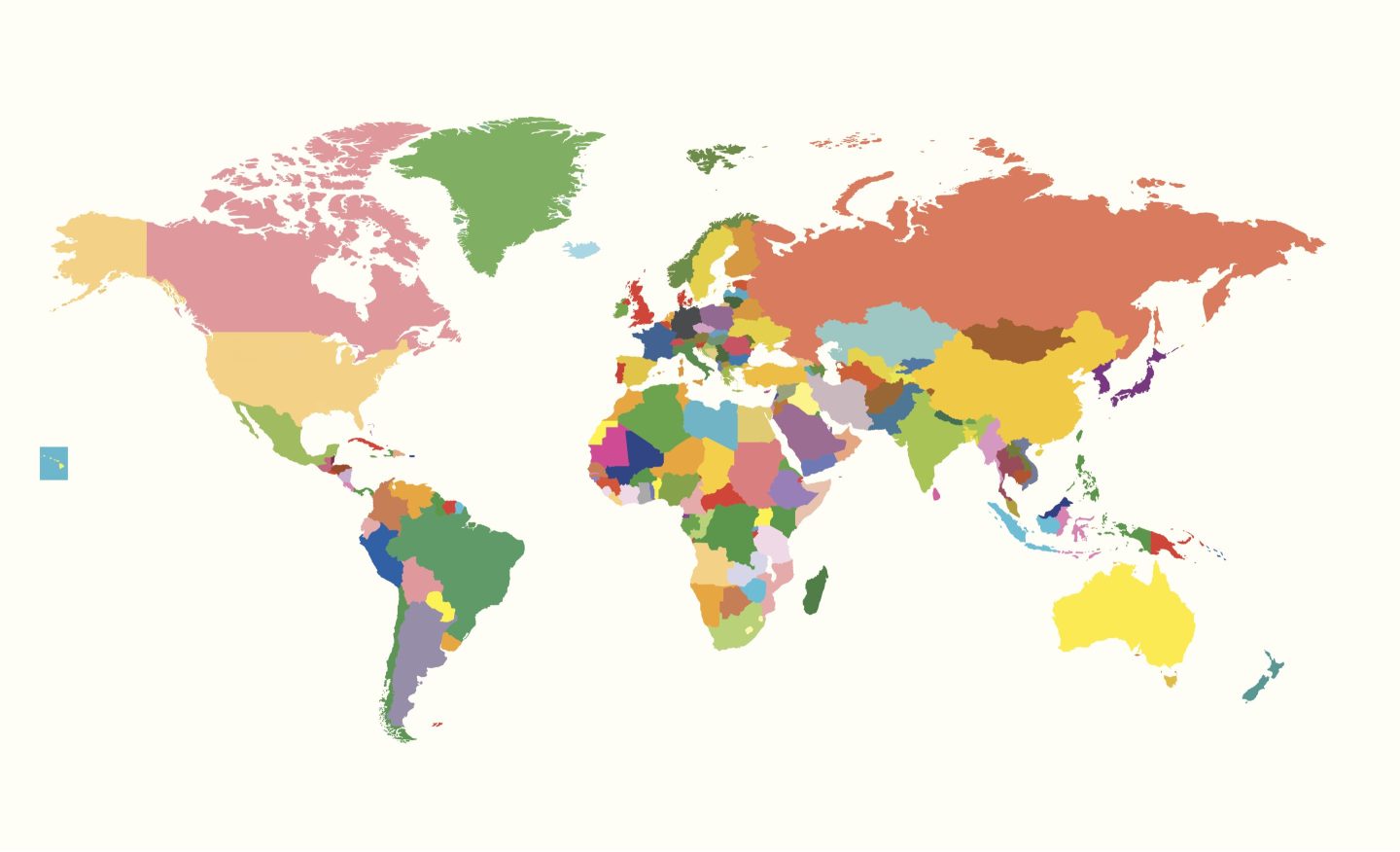

When it comes to hugeness, don’t negate the distorted perspective of maps. The Mercator global maps that Trump and many others grew up with, like the one below, show a Greenland that’s appears to be almost as large as all of Africa. In fact, Greenland is one-fourteenth the size of Africa, although it’s still of course quite large (more than triple the geographic footprint of Texas).

Getty Images

“We try to rationalize irrational behavior. This is classic Trump ego politics,” said Humpert of The Arctic Institute. “It’s about him putting a Trump tower in Nuuk and saying he made the U.S. larger than any other president.”

Militarily, Humpert is quick to point out that China and Russia have more ships and submarines traveling near Alaska’s coast than Greenland’s ice. “There’s some truth to the Arctic heating up and there being more power politics in the Arctic,” he said. “But the [U.S.] should take care of its own backyard first.”

Silbey agreed. Offshore of Greenland represents one of the fastest routes between the U.S. and Russia, but existing defense treaties with Denmark give Trump all of the necessary military access for bases and waterway patrols. From a foreign policy standpoint, he said, annexation “is just categorically dumb. You’re blowing up NATO for access you already have.”

A potentially more cynical view comes from Daniel Immerwahr, foreign relations historian at Northwestern University. Immerwahr says Trump is abandoning the U.S.’s long-standing soft power diplomacy approach—the U.S. maintains 750 military bases in other countries—that was intended to avoid wars over land and resources, and is now focusing on the old-school colonialism of ownership and control, especially in the Western Hemisphere

“It may be that we’re entering a world of closed borders, in which case it makes more sense for security reasons to lock down the territories that contain the things you need because you might be afraid some other country would close trade lines,” Immerwahr said, citing critical minerals as an example.

“China’s desires on Taiwan and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have corresponded to the more closed annexationist model,” he added. He also noted that a U.S. seizure of Greenland might be seen as a green light for China and Russia to follow suit in their own spheres of influence.

Trump has repeatedly insisted that, if the U.S. doesn’t acquire Greenland, then “Russia or China will take it over” and exploit its resources and strategic military positioning. But China has invested in many projects in Greenland that have mostly failed, and has largely pulled out since, said Adam Lajeunesse, chair in Canadian and Arctic policy at St. Francis Xavier University in Nova Scotia.

There’s no logic to a Chinese or Russian takeover, especially when Greenland has U.S. and NATO military backing, he said.

“That’s a myth,” Lajeunesse said. “The economic bogeyman the Trump administration is putting out there is really quite fictitious.”