Just as the Supreme Court tends to stay open when a two-inch snowfall in Washington terrorizes the snowflakes of the federal Office of Personnel Management and closes the executive branch, the budget impasse that has shut down much of the federal government has not kept the court from opening its new term on schedule today.

The court’s Public Information Office has been answering queries with a statement that exudes a certain air of, “If you must ask, yes, of course we are open.”

Officially, the statement is, “At this time, the Court will continue to conduct its normal operations and no change to the Court’s schedule for the October session is anticipated. The Court will rely on permanent funds not subject to annual approval, as it has in the past, to maintain operations through the duration of short-term lapses of annual appropriations.”

Tourists even had the option of visiting the court building last week, which was open after the federal shutdown began. Today, the public spaces were to reopen after the first two arguments of the term were completed (which is the norm on an argument day).

The court’s cafeteria is busy at breakfast, serving omelets (they’re pretty good, if I may say so) and other options such as breakfast burritos, avocado toast, and oatmeal. The lunch specials are posted for the week, and today’s “Sizzle” special is a Buffalo chicken wrap.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett, in some of her public appearances last month to promote her book, “Listening to the Law,” was asked about her time as the court’s junior justice, which included the traditional role as the leader of the court’s cafeteria committee.

“It’s the job of the junior justice to supervise the cafeteria,” she told Fred Ryan at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library on Sept. 9. “I don’t have to do that anymore, now it’s Justice [Ketanji Brown] Jackson.”

Barrett noted the tradition of the new justice putting her mark on the cafeteria’s offerings in some way.

“I really wanted to have Starbucks in the cafeteria,” Barrett told Ryan, adding that the well-known brand is now served in the ground-floor eatery that was renovated around the time of the Covid-19 pandemic.

(Justice Elena Kagan was known for having brought a frozen yogurt machine, while Justice Brett Kavanaugh was responsible for a quick-heating pizza oven. If Jackson has made her imprint on the cafeteria yet, she hasn’t publicly taken credit for it.)

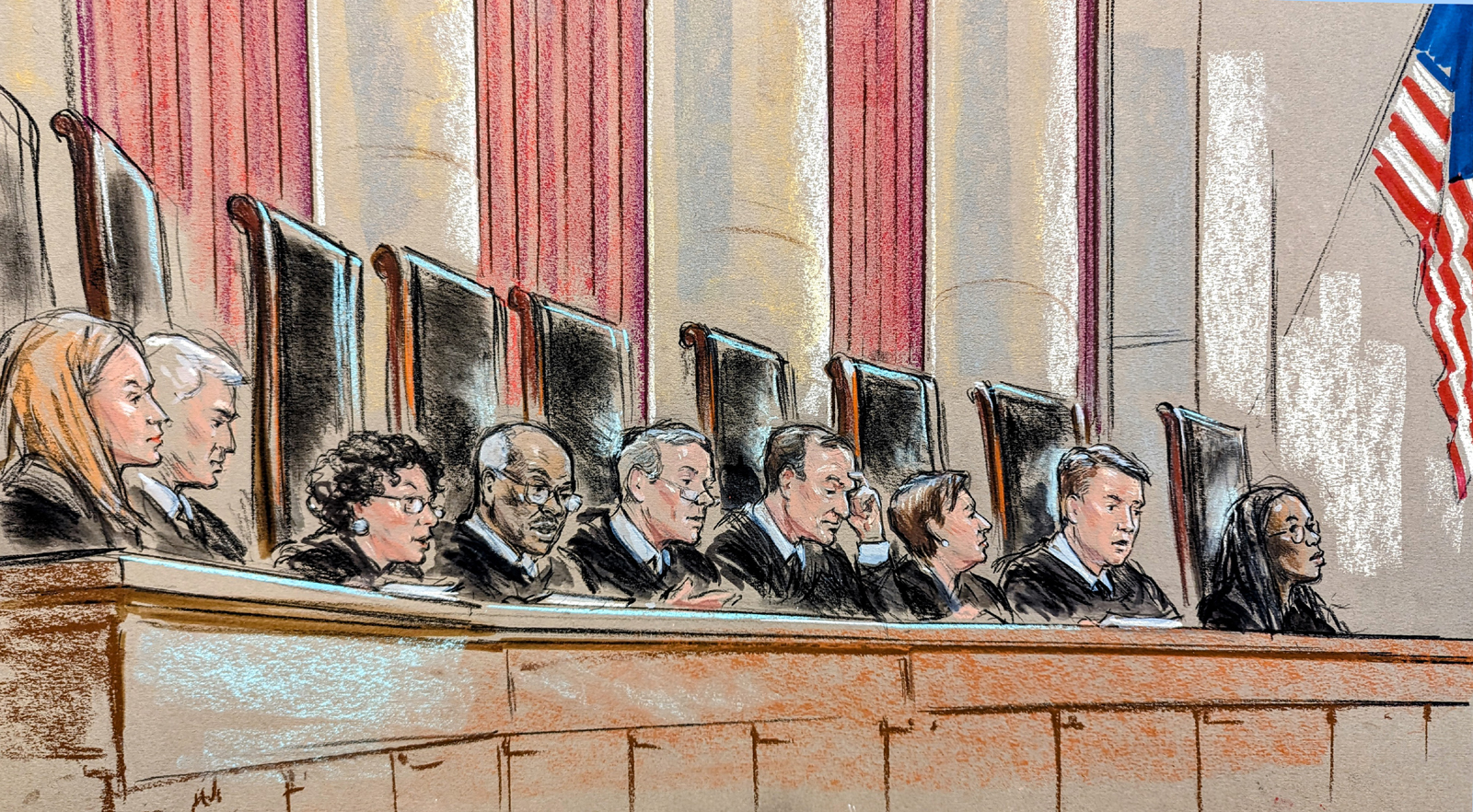

In the courtroom, both the bar and public sections are reasonably, if not completely, full. U.S. Solicitor General D. John Sauer is here today, but otherwise the courtroom is short of star power.

A little after 10 a.m., the justices take the bench, presumably having eaten a healthy breakfast, whether from the cafeteria or not.

The first case for argument of the new term is Villarreal v. Texas, about whether a trial judge may prohibit a defense lawyer from discussing trial testimony with his client when there happens to be an overnight recess in the middle of that testimony.

Stuart Banner of UCLA Law School’s Supreme Court Clinic is representing Villarreal, who was apparently high on meth and gripped by paranoia when he stabbed his boyfriend, Aaron Estrada, to death.

During the trial, Villarreal testified in his own defense before the court called an overnight recess. The judge barred Villarreal’s attorneys from conferring with him about his testimony during the recess, saying they wouldn’t be able to do so while he was on the witness stand.

Villarreal was convicted, and on appeal, he argued that the judge’s ban violated his Sixth Amendment right to effective assistance of counsel. Texas appellate courts ruled against him.

“During an overnight recess, the defendant and his counsel have a lot that they need to talk about,” Banner says in opening his argument. “They need to go over the testimony that took place that day. They need to prepare for the testimony that is going to be given the next day. These are basic discussions that any competent lawyer would have with the client. This is the assistance of counsel that the Sixth Amendment guarantees.”

Banner faces a tough grilling from the justices, who ask him about where this case falls between two key Supreme Court precedents, Geders v. United States, a 1976 decision that said a judge’s order to a lawyer not to confer with his testifying client “about anything” during an overnight recess violated the Sixth Amendment; and Perry v. Leeke, a 1989 decision that upheld a similar order between lawyer and testifying defendant during only a 15-minute midday recess.

Jackson presses Banner on “a critical point, which is, to the extent that the lawyer couldn’t manage, coach, prep, practice … with the witness while he’s on the stand, why should he be allowed to do so during an overnight recess?”

Jackson is perhaps the only member of the court who has regularly represented criminal defendants, though her role in a federal public defender’s office was as an appellate attorney, not a trial lawyer.

But still, this is the kind of lawyerly case that seems to strike a professional chord with the justices.

Chief Justice John Roberts wonders how attorney-client privilege would play out with such an order. Could a prosecutor cross-examining a defendant ask what he and his defense lawyer spoke about during the overnight recess, Roberts asks.

“Objection, Your Honor, attorney-client [privilege],” Roberts suggests the defense lawyer would quickly say, though he worries that would not be a “reasonable counterweight to the problems” raised by the case.

This future episode of “Law & Order” practically writes itself.

The chief justice calls on Assistant Criminal District Attorney Andrew Warthen of Bexar County, Texas, to begin his argument. Warthen’s voice is soon heard, though no one is at the lectern.

I strain to see that Warthen is in a wheelchair at the counsel table. He tells me via email later that by a stroke of bad luck, his back went out this morning just after he had arrived at court and reached down for a binder. The court’s nursing unit came to his aid, and the Marshal’s Office arranged for him to argue from the table instead of the lectern.

Warthen is apparently the first lawyer to argue before the court from a wheelchair since then-Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott, who is paralyzed from the waist down, did so in 2005 in Van Orden v. Perry. (The court allowed a Ten Commandments display on the grounds of the Texas State Capitol to remain in place.)

Warthen’s back pain does not keep him from making a strong argument, which appears to get traction from several justices.

“When the defendant’s testimony is paused for a long break, the trial court may tell defense counsel not to either manage the ongoing testimony, as we propose, or not to discuss the testimony altogether, as the United States proposes,” Warthen says in his opening, highlighting some daylight between Texas’s position and that of the solicitor general’s office, which will soon argue as a “friend of the court” in support of its more absolute rule.

Kagan presses him about a defendant who mumbles and fails to make eye contact with jurors. Could the lawyer advise him to do better on those things during an overnight recess?

No, Warthen says, because that would be coaching his testimony in violation of the judge’s order.

Kevin Barber, an assistant to the solicitor general, argues for the United States in favor of that broader rule, barring the discussion of any testimony.

“We think that’s a clear and workable line,” he says.

One of Barber’s answers gets some discussion in the press room after the argument. Jackson presses him about why the court should go further when Warthen’s suggestion that any further bar on managed testimony would satisfy the Sixth Amendment.

“I think that just because this order satisfies the Sixth Amendment doesn’t mean that a somewhat broader order could not,” Barber says, “especially when we account for the fact that trial judges can be trusted to tailor these orders depending on the specific nature of the case, the nature of the defendant, the nature of defense counsel.”

So, it is apparently the official legal position of the United States that trial judges, presumably including federal district judges, can be trusted to properly tailor their orders. Noted.

Tuesday will bring two more arguments, including in Chiles v. Salazar, in a term shaping up as a big one. Of course, an extended federal budget impasse may eventually have an effect on operations.

But for now, all is relatively normal. For all those authorized to be in the building on the mornings of an argument day, breakfast begins at 9 a.m.

Cases: Villarreal v. Texas

Recommended Citation:

Mark Walsh,

The court opens for business despite a federal shutdown,

SCOTUSblog (Oct. 6, 2025, 7:42 PM),

https://www.scotusblog.com/2025/10/the-court-opens-for-business-despite-a-federal-shutdown/