Based on Hunterbrook Media’s reporting, Hunterbrook Capital is long $JMIA at the time of publication. Positions may change at any time. See full disclosures below.

LAGOS, Nigeria — This year’s most captivating Black Friday story may be thousands of miles from America’s midnight campouts and flatscreen fistfights.

On a late November day in Isolo, on the industrial outskirts of Lagos, Jumia’s main warehouse in Nigeria looked less like a sterile corporate operation and more like a humming ecosystem trying to keep up with a nation’s worth of orders. The compound spans 30,000 square meters and every corner pulsed with the urgency of Black Friday, a concept Jumia first brought to the continent over a decade ago.

Past the security gate, the honking of trucks and roar of planes from the nearby airport gave way to a blur of movement: workers in orange and green reflective jackets bending over computers, taping boxes, hauling sacks of rice, carting air conditioners, and shuttling refrigerators toward the outbound docks. Products rose in towers — washing machines, stoves, bags of grain — forming a skyline of demand.

“This is the busiest time of year,” said Richmond Carlos Otu, Jumia’s chief supply chain officer, citing the warehouse’s 24-hour work cycle. “Within this period and most times of the year, we run different shifts to ensure that people don’t burn out.”

Managing morale has become part of the logistics playbook. A canteen meal each day. Apples on Wednesday. A DJ on Friday. “As much as the period is high intensity for us,” Otu said, “it is also high reward… because we get a lot of customers or new people looking to try Jumia’s service for the first time, and they get their package.”

Olumuyiwa Olowogboyega, a Lagos-based tech and big business analyst, told Hunterbrook: “Jumia’s logistic infrastructure in Africa is pretty much unmatched for e-commerce.”

A few miles away, on Olumo Street in Yaba, a suburb of Lagos, a pickup station bears the Jumia name. Inside, staffers scramble to locate packages. Vendors drop off wigs, air conditioners, and plate racks. Customers jostle to collect orders.

This holiday season, Ayomide Olajide tells Hunterbrook she ordered 12 items from Jumia, including a body cream and a smartwatch she gave as a gift.

“It is about the discounts,” she said.

The scene at that pickup station in Yaba, and that warehouse in Isolo, is about something else, too: a company that refused to die.

For almost a decade, Jumia had been the poster child for tech bro hubris exported to the wrong latitude. Dubbed the “Amazon of Africa” at its 2019 IPO, the company burned through over a billion dollars trying to push a Western model of door-to-door convenience onto a continent with struggling infrastructure and strapped budgets — led by armchair executives in Dubai and Paris.

The stock lost more than 95% of its value, from over $60 in February 2021 to under $2 in April 2025.

Compounding Jumia’s challenges, the Chinese e-commerce giants Temu and Shein descended upon Africa, armed with deep pockets and aggressive algorithms. The picture for Jumia seemed bleak. “Nobody thought we would make it through winter,” the company’s CEO told Hunterbrook in an interview.

But after a corporate coup, the sweeping removal of the old growth-at-all-costs regime, and a pivot that forced executives to relocate to Africa and rebuild the company around what customers actually wanted, Jumia is back.

Data, local reporting, and detailed research suggest that Jumia has fended off Temu and Shein. And now, for the first time, the company appears to be growing sustainably — projecting profitability by 2027 — capitalizing on a rebounding macroeconomic environment that has turned headwinds into tailwinds.

This Black Friday is not just a sale. It could be the proof of concept for a business that might finally be ready to win the final frontier of e-commerce.

“We could be the small Mercado Libre of Africa,” said Dufay, referring to $MELI, which pioneered a similar model in Latin America, and now has over a $100 billion market cap. Jumia is valued at around $1.3 billion, with shares trading just below $12 at the time of publication.

The next update to investors will likely come in early December — when, if the pattern from last year continues, Jumia will release its Black Friday sales numbers.

“We all tell ourselves internally that, in November, nobody sleeps,” Temidayo Ojo, who leads Jumia’s Nigeria business, told Hunterbrook. “And then, after Black Friday, we all catch up on sleep.”

Sign Up

Breaking News & Investigations.

Right to Your Inbox.

No Paywalls.

No Ads.

The Armchair Leadership Era — And Its Exception

Jumia’s descent was defined by distance.

Until late 2022, Jumia’s highest-paid employees were largely based in Dubai and Paris. Executives flew into African capitals for high-level meetings, pushing a strategy of growth at the expense of margins. Venture capital subsidized sales to boost topline numbers amid fraud accusations. Jumia Food attempted to race hot meals through gridlocked traffic on motorbikes. It cost over a billion dollars — and the business model broke.

But Côte d’Ivoire told a different story — under the leadership of Francis Dufay, who had moved to the city of Abidjan to run the operation.

His playbook:

- Pickup stations for areas where last-mile delivery can be expensive and unreliable.

- Expansion out of major cities to underserved “upcountry” areas.

- Lowering prices, even if that meant eschewing name brands.

“I was living here in Abidjan talking to people who actually make those $200 a month,” Dufay told Hunterbrook, contrasting his on-the-ground approach with the remote leadership of the company. “You cannot see eye to eye with people sitting far away from the continent who had never lived there.”

What Dufay learned, he said, was that customers were willing to trade convenience for affordability.

While Jumia’s headquarters pushed L’Oréal and Nike, he was happy to tap into the “huge pockets of demand absolutely not served by retail.”

That meant selling $5 off-brand shoes instead of $50 Adidas; $60 functional phones instead of the latest iPhones. “We did that with just no ego,” he said.

Dufay’s approach worked: Even as Jumia struggled across the continent, in Côte d’Ivoire, the company took over almost the entire e-commerce market, with sustainable financials.

So when Jumia defenestrated its failed leadership team in 2022, with its stock below $5, it was no surprise that the board turned to Dufay to take over the whole company and bring his strategy from Côte d’Ivoire to the rest of the continent.

He shuttered the Dubai headquarters and forced management to relocate to the markets they served. He killed Jumia Food. He slashed expenses, including firing a large chunk of the team, a decision he described in an interview with Hunterbrook as “hell.”

But his most significant move was a philosophical pivot: shifting the value proposition of Jumia’s platform. Jumia’s new thesis was that if it could offer everyday goods cheaper than competitors — and build trust with high-level customer service — the the business would work.

Cash burn fell. Unit economics improved. After quarters of decline, Jumia began growing revenue and GMV again.

GMV (Gross is the total dollar value of all goods sold through an online marketplace, before subtracting costs, discounts, or returns. It’s the core metric used to measure the overall scale and growth of an e-commerce platform.

The bleeding stopped — and, suddenly, Jumia had the operating leverage needed for a potential turnaround.

The Trust Moat

In the United States, e-commerce is built on the assumption of a paved road to every doorstep, trust in the delivered product, and low rates of lost or stolen packages. It made up over 16% of all 2Q25 retail sales.

In many African countries, the last mile of delivery is often a dirt path, a confusing alleyway, or a gated compound. Jumia estimates e-commerce penetration at around 3%.

Against this backdrop, delivering a $10 package to a specific door in rural Kenya can destroy the unit economics of the transaction. With Dufay as CEO, the company aggressively shifted its focus to the network of pickup stations he’d implemented in Côte d’Ivoire, where he still lives.

It was an idea Dufay says came from a local supply chain manager. “Door delivery is complex, expensive, hard to run, and expensive for customers,” Dufay explained. It added up to an extra $1.50 to $2 per delivery. “If you make $200 a month, you’re very happy to save a dollar and walk for 20 minutes.”

By consolidating deliveries into thousands of physical points — often partnerships with local mom-and-pop shops or gas stations — Jumia delivered immediate results: The cost per order plummeted from the unsustainable high of $3.50 in 2022 to $2.10 by 2025. The amount of money Jumia spends on marketing per order also fell, from $2.90 per order in 2022 to $0.90 per order as of last quarter.

But the pickup station network — which now appears to include more than 1500 locations — solves a deeper problem than cost: trust.

“The reality is that the African customer does not trust e-commerce,” explained Abubakar Idris, a business journalist from Nigeria who manages Cornell University’s student-led Cayuga Fund as an MBA candidate. “They are concerned that the quality is much lower.”

Dufay echoed this sentiment: “Those pickup points also have a huge positive impact in terms of marketing, and making the brand real in areas where people have no idea what e-commerce is,” he told Hunterbrook.

“It made us very real, very legitimate, and it opened the door to a whole new pool of customers — literally people pushing through the door and asking, ‘I want a fridge. I have no idea what you’re doing, but I know you have fridges. Explain it to me.’”

In a world rife with Instagram scams and counterfeit vendors, the pickup station also acts as a form of credibility. A customer can walk into the shop, see the box, and pay in cash or via mobile money only upon collection. This physical touchpoint bridges the gap between the digital promise and the physical reality, delivering security even the best algorithmic ads cannot provide.

That physical footprint is also exactly what Jumia’s international competitors lack.

Taking on Global Goliaths

By the time Temu entered Africa in 2024, four years after Shein, the local industry was bracing for impact.

In Nigeria, Temu ads were unavoidable. It became the most downloaded app in the country. But it also irked some people, who complained about the onslaught. One social media observer said Temu could “hunt you in your dreams.” Temu even offered $100 vouchers.

“It was annoying,” Isaac Ayodele, a longtime Jumia customer, recalled. “They are saying the same thing over and over again.”

And Temu products weren’t always what they seemed, according to Hunterbrook’s reporting. “On Temu, if you are not careful and look at the dimensions of what you are going to get, you might end up getting a miniature size of what you want to get,” said Barakat Adebayo-Ige.

The issue is structural. The “Cross-Border” model used by Temu relies on shipping individual packages from China through global freight carriers.

This creates two frictions in Nigeria:

1) Payment: International players generally require prepayment via credit card. In Nigeria, banking penetration is low, and skepticism of online prepayment is high. That’s why Jumia allows customers to pay with cash upon delivery.

2) Returns: If a blender arrives broken in Lagos, shipping it back to China is economically challenging for the consumer. Hunterbrook has heard Temu often refunds customers — or sends a logistics partner to pick up a product a customer wants returned — but the infrastructural challenges are way more complex for Temu than for a regional company.

And it sometimes apparently takes longer for Jumia’s competitors to reach consumers in the first place.

Sabo Blossom likes to shop on Shein — “they just have a pinpoint on fashion stuff” — but she said that the delivery period is about two weeks. Jumia typically delivers within a week.

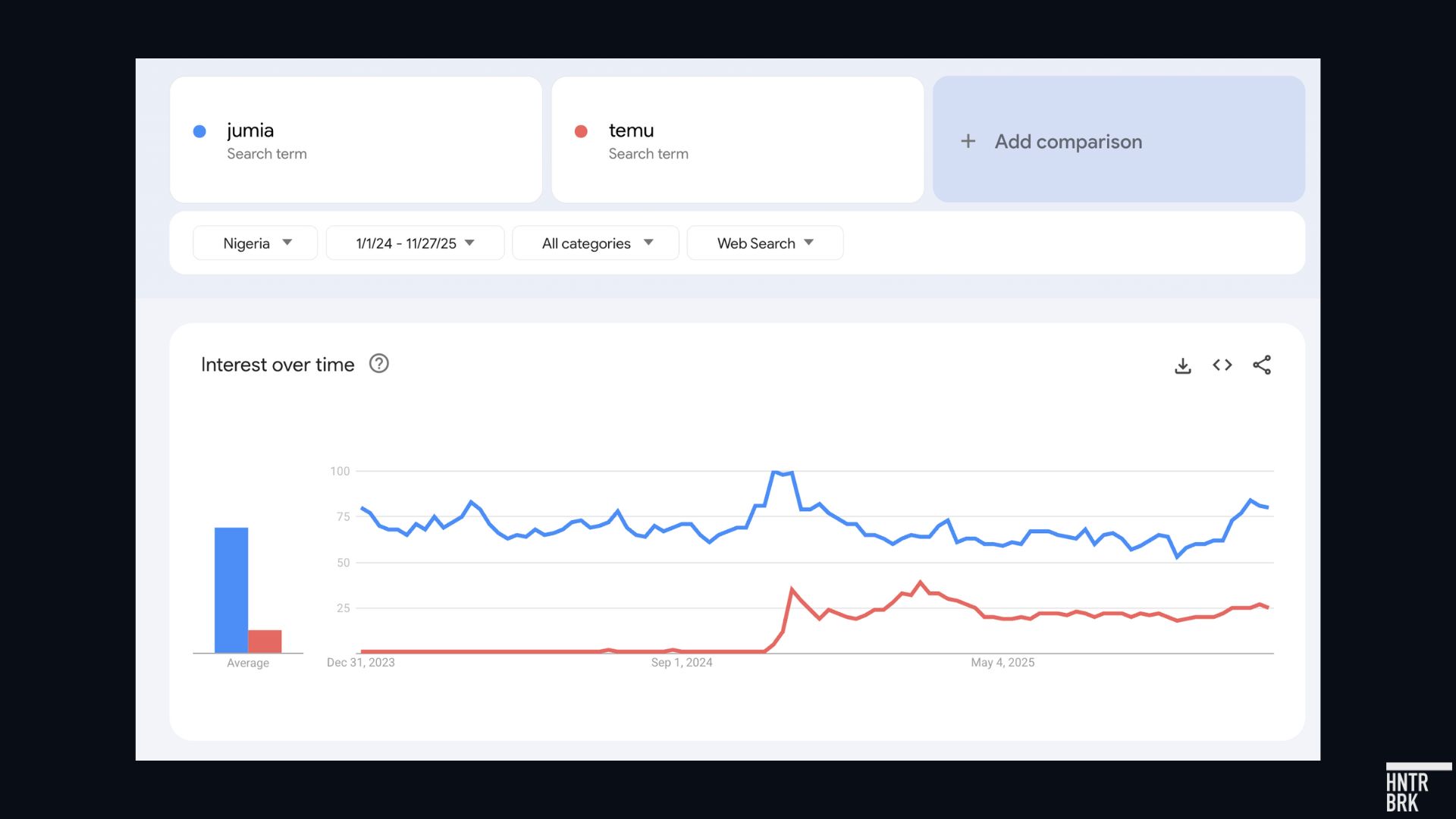

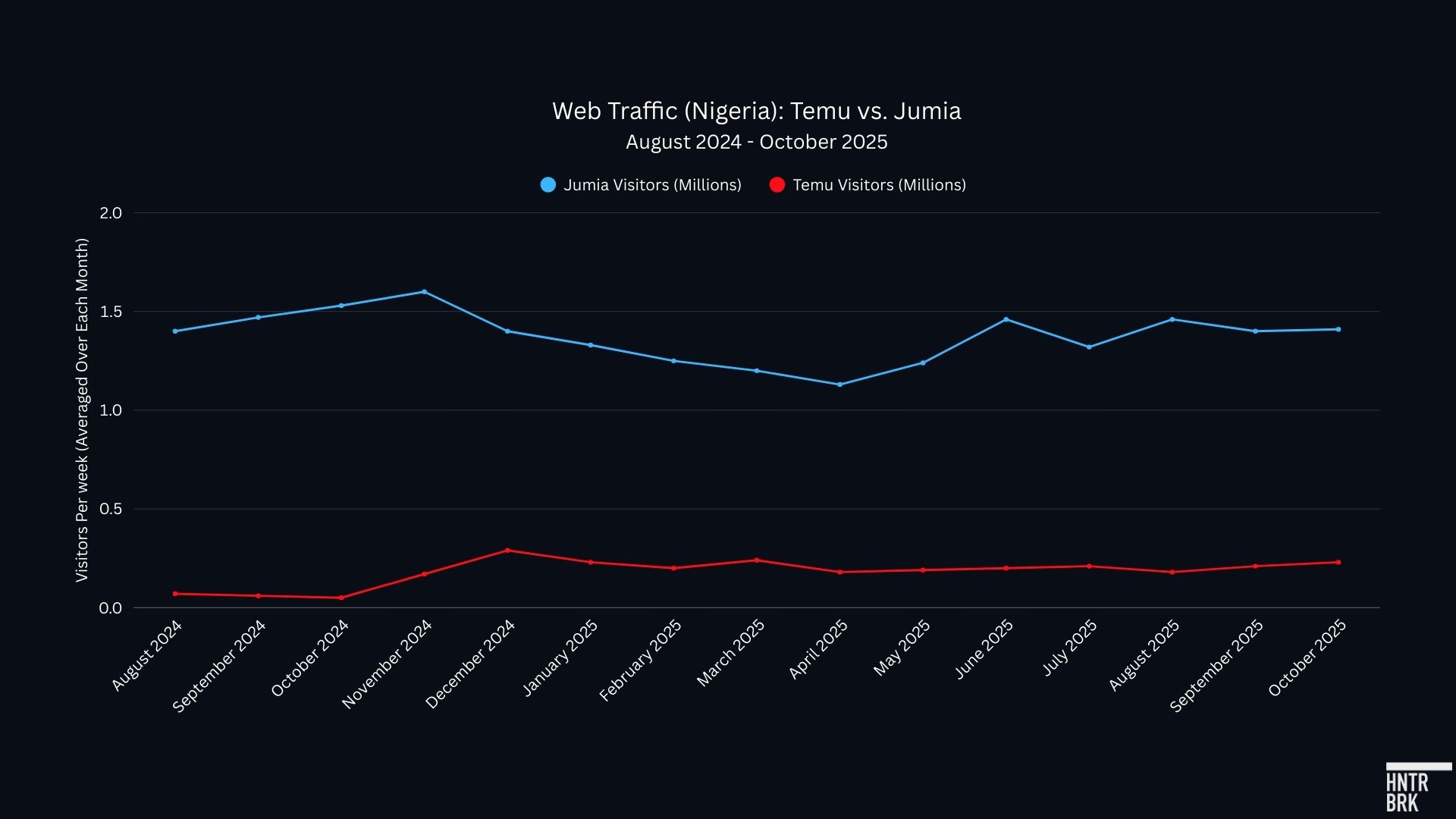

Despite all the advertising, web traffic and app retention data now indicate the Temu offensive has stalled, especially in Nigeria, Jumia’s biggest market. Google Trend data, which Dufay said has been a decent historical gauge of the company’s performance — and which the outlet Rest of World included in its own feature on Jumia — tells a similar story of Jumia maintaining its edge.

Jumia has pulled this off in part by undercutting Temu on price in some of its most critical verticals, with its products “60-70% cheaper than Temu on the same SKUs across their top-selling items,” according to data shared with Hunterbrook by an investor in Jumia.

Dufay shared a slightly more conservative figure with Hunterbrook, saying he believed, within the categories Jumia has prioritized, it is able to “beat them on prices pretty much 50-65% of the time.”

Temu, of course, offers a wider array of options. And it is indeed sometimes cheaper.

Adebayo-Ige, who described herself as an e-shopaholic and says she has not stepped into a physical store in years, has certainly seen this be the case: “There is a jewelry I am seeing right now on Jumia for 14,000 naira, I have seen the same jewelry on Temu for 5,000 naira. And I can beat my chest to it that it is going to be of the same quality,” she said.

But even in the instances when Temu has cheaper prices, it is facing difficulties across the continent when it comes to delivering a product customers actually want. “We’re coming with much better service,” Dufay noted. “We’re adapted to local customers. You can pay on delivery. You have someone to talk to — very important for Nigerian customers, always scared of getting scammed.”

Hunterbrook witnessed Jumia’s customer service efforts in its own experience on the platform. After starting but not completing an order on Jumia, within 30 minutes, Hunterbrook’s reporter heard from a member of the company’s “J-Force,” its army of sales consultants. These customer service representatives offer guidance on how to finish placing the order and discuss payment options.

Olowogboyega, the analyst, emphasized this difference from the Chinese e-commerce competitors. “For years, Jumia has done this pay-on-delivery mode that has somewhat really deepened trust in its primary market,” he said.

Dufay made a similar point. “We took the e-commerce playbook and it took us 12 years to make it very relevant for Africa. Could have been faster, right? Could have been much faster, but still, we’ve made it finally. And that creates significant barriers to entry, because anyone who would come to Africa with something that’s been successful in another continent would have a hard time.”

He says Temu may not be willing to update its approach in the same way. “They don’t see the need to adapt, right? They have bigger fish to fry. And so they’d rather just pull out if it’s not working than reorganize.”

He added: “The intern managing from Shenzhen has already relocated the marketing budget to another country.”

Temu — which has been accused of having forced labor in its supply chain, as Hunterbrook previously reported, accusations the company has denied — did not reply to repeated requests for comment.

Boosting Supply To Meet Demand

Historically, Jumia suffered from a supply deficit — regardless of demand, Jumia couldn’t keep enough products in stock at the right price. Dufay committed to changing this.

His gameplan included establishing dedicated sourcing in Shenzhen, China, with 62 Jumia staff across the country, according to Jumia’s investor presentation. The goal: bypass the middlemen.

By connecting Chinese factories directly to Jumia’s African warehouses, the company could offer goods at lower prices. The trend has been turbocharged by U.S. tariffs, which have led to a greater portion of China’s exports being directed to Africa rather than North America.

Jumia saw 55% growth year over year in the number of items sold on its platform from Chinese sellers, according to a recent investor presentation.

This has helped Jumia stock up for high demand events like Black Friday.

During its 2024 Black Friday campaign, Jumia generated 18% more orders than in 2023.

In 2025, the company seems focused on delivering an even bigger number.

Part of this will be making sure the platform’s demand can be met with adequate supply. A Hunterbrook analysis of data obtained via web scraping shows that the company added more than 10,000 new sellers between October and November.

This calculation is based on “SELLER ID” numbers listed on Jumia’s website. This does not mean each of these sellers is actively on the platform shipping products.

Asked directly whether Jumia could meet Black Friday demand, Dufay said “absolutely.”

“We’ve done three years of hard work to rebuild,” Dufay said of the supplier network. “The macro is finally in our favor, so importers are importing again because there’s less volatility.”

At least one of Jumia’s suppliers has seen firsthand how the limits are being tested. Hunterbrook spoke to a source who received data from one of the leading smartphone sellers in Nigeria. Last November, the supplier reportedly measured 416,000 of its daily users active on the Jumia app; this November, that number is 600,000.

Jumia has staffed up to meet the holiday demand. “We have a mix of temp teams that we onboard just for the event,” said Ojo, the CEO of Jumia Nigeria. “Onboarding and training for Black Friday started in October, the second week of October, bringing people in, particularly on supply chain operations.”

“We are seeing very encouraging, very very very encouraging numbers,” he added, “and we are also getting feedback from consumers and sellers that they are quite happy. ”

Macro Headwinds Become Tailwinds

Jumia fought uphill through most of the 2010s.

Currencies crashed. Inflation crushed purchasing power. Importing goods in dollars while earning in naira was a losing proposition. “It was probably the worst macroeconomic environment we’ve had in Africa for decades,” Dufay said. “Not one decade — multiple decades.”

In 2025, the currents began to reverse:

- Nigeria’s economy stabilized after painful reforms, prompting a Moody’s upgrade and easing the currency volatility that once destroyed Jumia’s margins.

- GDP growth in Jumia’s core markets is inching back toward 3.5–4%.

This comes alongside broader positive macro trends:

Africa is becoming the kind of environment where e-commerce can work.

Success is not guaranteed. Both Dufay and Ojo cited regulatory uncertainty as potential risks to the business. And many of the countries where Jumia operates have undergone significant political tumult in recent years. Just this week, there was a military coup in Guinea-Bissau, which borders Senegal, one of Jumia’s markets.

But there’s no doubt that internet adoption across the continent is on the rise, in a pattern that in some ways mirrors the launchpad of other regional e-commerce success stories, like Mercado Libre ($MELI) in Latin America and Sea Limited ($SE) in Southeast Asia and Brazil.

According to a Jumia analysis, Latin America’s e-commerce penetration grew from 2% in 2012 — around where Jumia’s markets in Africa stand today — to an estimated 14% in 2025. Asia Pacific leapt from 5% in 2012 to an estimated 28% in 2025. Jumia is betting that Africa will experience a similar inflection. (Ojo told Hunterbrook he hopes e-commerce adoption will rise in Jumia’s markets from the low single digits into the double digits in the next five years.)

If Jumia can seize the opportunities before it, the company says, it will grow revenue meaningfully without sacrificing its margins; achieve full-year profitability by 2027 without needing to raise capital; and generate several billion a year in GMV by 2030.

The north star no longer appears to be becoming the next Amazon, whose market cap is around an order of magnitude larger than Nigeria’s entire gross domestic product. It’s now about becoming the best possible version of Jumia — and seeing where that can take them.

Dufay says he doesn’t want to get ahead of himself — as a pragmatic “glass-half-empty kind of guy.” He began his interview with Hunterbrook saying he felt “tired” and “sick” amid the end of year sprint, a stark contrast from the promotional, hypebeasty approach of the public company CEOs Hunterbrook often covers.

And yet, it was hard for Dufay to temper his excitement. When asked about where Jumia could be on the other side of this turnaround, Dufay painted a future with billions in sales, millions more customers, and the operating leverage to serve them all profitably.

“In the past, this company went for optionality way too early, but when we finally have this core business at scale,” he said, “we can do anything.”

Pelumi Salako is an independent journalist based in Lagos, Nigeria. He covers development, culture, technology, security, human rights, global health, and climate change in Nigeria and across West Africa for Al Jazeera, The Associated Press, The Guardian, National Public Radio, Devex, The Thomson Reuters Foundation, The Telegraph, and Foreign Policy amongst several other global newsrooms. He received the 2023 Future Africa Award for Journalism for his excellence in storytelling and impactful reporting, and is a 2025 United Nations Reham Al-Farra Journalism Fellowship.

Sam Koppelman is a New York Times best-selling author who has written books with former United States Attorney General Eric Holder and former United States Acting Solicitor General Neal Katyal. Sam has published in the New York Times, Washington Post, Boston Globe, Time Magazine, and other outlets. He has a BA in Government from Harvard, where he was named a John Harvard Scholar (taking much easier classes than Dhruv!) and wrote op-eds like “Shut Down Harvard Football,” which he tells us were great for his social life. Sam is based in New York.

Jim Impoco is the award-winning former editor-in-chief of Newsweek who returned the publication to print in 2014. Before that, he was executive editor at Thomson Reuters Digital, Sunday Business Editor at The New York Times, and Assistant Managing Editor at Fortune. Jim, who started his journalism career as a Tokyo-based reporter for The Associated Press and U.S. News & World Report, has a Master’s in Chinese and Japanese History from the University of California at Berkeley.

Hunterbrook Media publishes investigative and global reporting — with no ads or paywalls. When articles do not include Material Non-Public Information (MNPI), or “insider info,” they may be provided to our affiliate Hunterbrook Capital, an investment firm which may take financial positions based on our reporting. Subscribe here. Learn more here.

Please email ideas@hntrbrk.com to share ideas, talent@hntrbrk.com for work, or press@hntrbrk.com for media inquiries.

LEGAL DISCLAIMER

© 2025 by Hunterbrook Media LLC. When using this website, you acknowledge and accept that such usage is solely at your own discretion and risk. Hunterbrook Media LLC, along with any associated entities, shall not be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages resulting from the use of information provided in any Hunterbrook publications. It is crucial for you to conduct your own research and seek advice from qualified financial, legal, and tax professionals before making any investment decisions based on information obtained from Hunterbrook Media LLC. The content provided by Hunterbrook Media LLC does not constitute an offer to sell, nor a solicitation of an offer to purchase any securities. Furthermore, no securities shall be offered or sold in any jurisdiction where such activities would be contrary to the local securities laws.

Hunterbrook Media LLC is not a registered investment advisor in the United States or any other jurisdiction. We strive to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information provided, drawing on sources believed to be trustworthy. Nevertheless, this information is provided “as is” without any guarantee of accuracy, timeliness, completeness, or usefulness for any particular purpose. Hunterbrook Media LLC does not guarantee the results obtained from the use of this information. All information presented are opinions based on our analyses and are subject to change without notice, and there is no commitment from Hunterbrook Media LLC to revise or update any information or opinions contained in any report or publication contained on this website. The above content, including all information and opinions presented, is intended solely for educational and information purposes only. Hunterbrook Media LLC authorizes the redistribution of these materials, in whole or in part, provided that such redistribution is for non-commercial, informational purposes only. Redistribution must include this notice and must not alter the materials. Any commercial use, alteration, or other forms of misuse of these materials are strictly prohibited without the express written approval of Hunterbrook Media LLC. Unauthorized use, alteration, or misuse of these materials may result in legal action to enforce our rights, including but not limited to seeking injunctive relief, damages, and any other remedies available under the law.