Growing up in the 1990s in tiny Mansura, about 30 miles southeast of Alexandria, Annie Gauthier dreamed of becoming a historian and later toyed with the idea of law school.

But deep family ties and industry disruptions after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005 brought her back to central Louisiana to help run the chain of gas stations and convenience stores founded by her grandfather in 1970.

Today, that company, which does business as Y-Not Stop, has 15 locations, supplies another 25 gas stations with fuel, and does more than $100 million in annual sales, making it one of the largest companies in central Louisiana.

Gauthier, who shares the title of co-CEO with her brothers, also is emerging as a leader in the national industry. In October, she was elected chair of the National Association of Convenience Stores, which represents the more than 150,000 convenience stores across the U.S.

The convenience store industry is bigger than many realize. C-stores account for four out of every five gallons of fuel sold across the country and conduct 160 million transactions a year, generating more than $906 billion in annual sales.

In many rural communities, the convenience store is the only store for miles around.

And while major chains like Circle K, 7-Eleven, Casey’s and Speedway have tens of thousands of locations, 60% of convenience stores in the U.S. are single-store operations.

From her twin vantage points, Gauthier, who owns Y-Stop with her two brothers, has a unique perspective on the important role convenience stores play in the economy of many communities and the pressures they face.

In this week’s Talking Business, she discusses changes in the industry and the key to running a successful business with family members.

Interview has been edited for clarity and length.

How have customers’ expectations evolved over the last couple decades?

I think people expect more than they’ve ever expected, both from customers and from employees. We’ve been in food service for a long time, so I know an evolving expectation nationwide has to do with consumers willingness to seek convenience store food as a destination. In the South, as long as you fry things, people will typically eat them. And we’ve been frying things for 35 years, but we’ve seen more demand for fresh products and for unique products. People eat at least three times a day, so we’ve been able to lean into that and tailor our offer to evolving needs.

We’re constantly evaluating what people want, what they think they want, what they say they want but really don’t want, and trying to make sure that we can meet our customers where they are. I think most people, certainly our target customer, want to shop in a bright, open, clean, safe store with friendly staff. That’s something we’ve leaned into.

What kind of concerns do you hear from NACS members and what do they need from you?

A lot of people in our industry have historically experienced NACS as an event and know us best for our trade show each year, which draws about 25,000 people to learn about new products and hear education sessions on trends or governmental relations. A lot of people look to NACS for policy and to protect the industry from unnecessarily burdensome regulation.

As far as specific issues, they run the gamut — from fuel to technology, privacy and labor issues. NACS government relations staff is fond of saying that we have more issues than National Geographic. We’re selling food, we’re selling fuel, we’re selling alcohol, tobacco — in our case, we sell ammunition — we’re selling so many regulated products. We have loyalty apps, and there’s increasing regulations around AI and pricing and algorithms and privacy. How do we maintain compliance? How do we sell our customers the things they want to buy, and sell legal products on a level playing field?

How do state and federal regulations affect smaller chains compared to the big ones?

Smaller operators are less likely to have a dedicated government relations staff. When we smaller operators go to speak with regulators or elected officials, we can show up and have a more holistic experience of our business (than larger chains do) and we are able to tell that story. We’re the ones writing the payroll checks and interfacing with that government regulator. I think it can be harder for smaller operators to keep up with the constant onslaught of regulation and potential regulation, and how to tell their story and understand how regulations affect us. We don’t have the resources to comply as easily or be aware of compliance.

What is one of the biggest things about the convenience store business that people generally don’t understand?

One of the biggest surprises we’ve seen — certainly with employees as we hire them over the years and they learn more about how our business works — is understanding the fuel infrastructure. Nobody really ever thinks about where the fuel comes from. You pull up to a gas pump and just expect that there’s going to be fuel. It’s kind of like getting water out of a faucet. You don’t think about how it got there.

The reality is there’s limited tank capacity and it’s not like any other inventory product. If there’s a good deal on Snickers bars, you can buy extra boxes of Snickers bars and stick them in the back room. You can’t buy in extra fuel. You’re limited by your tank capacity, but you better not run out.

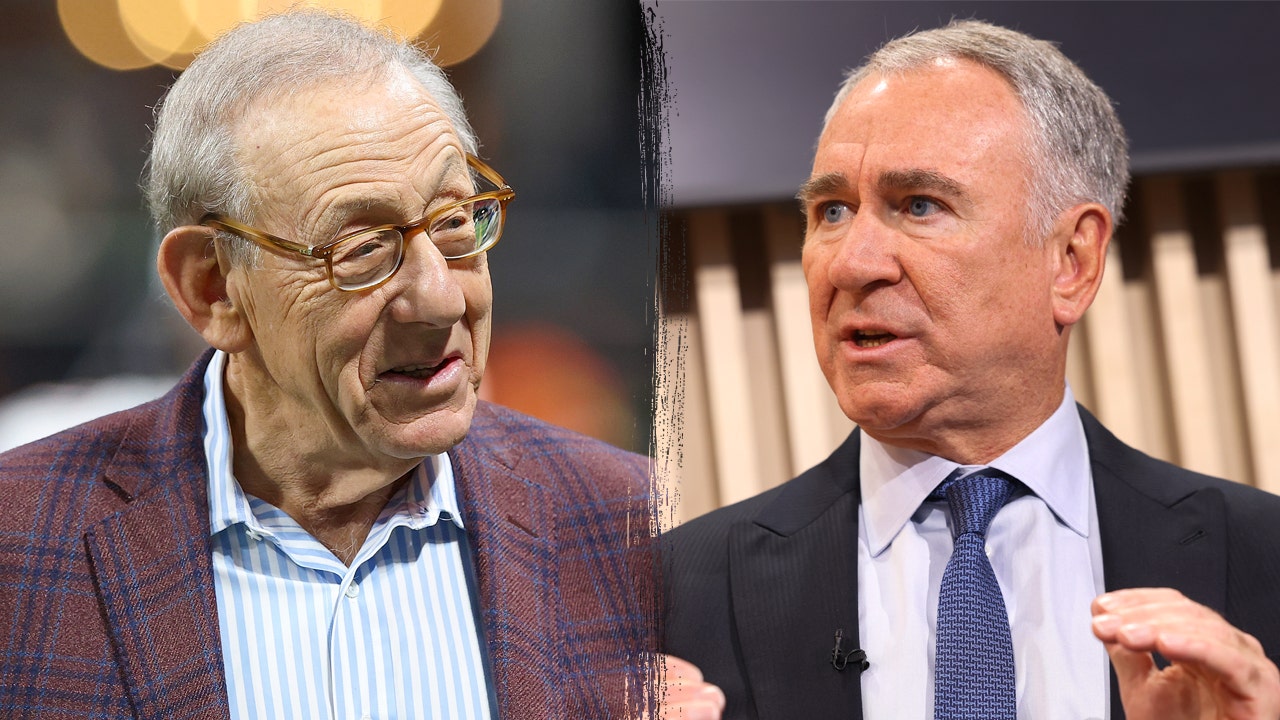

Pictured at the Oakdale Y-Not Stop store, St. Romain Oil’s third generation of family ownership is comprised of siblings, from left, Nick St. Romain, Annie St. Romain Gauthier and Zack St. Romain.

What advice would you give to someone thinking of going into business with their family, or starting to work in a family business?

Two things have served us well. One is role clarity. We are a family-run business, but we have a structured org chart. Each of my brothers and I have a different purview, and everybody in our company ultimately reports up to one of us.

The second thing is boundaries. We have to agree sometimes to not be at work. We call it “clocking out.” When we’re together on the weekends, with family or whatever, if one of us starts to talk shop, we’ll agree to table the conversation until we’re at work. It’s important to differentiate family mode and work mode. Otherwise, it can be easy for work to encroach into your whole life.