6

By Dr. Gaurav Ganguly, Head of International Economics, Moody’s

Attempts by the United States to vigorously change international economic and geopolitical systems have created high uncertainty this year, but the global economy has held up. Several countries have seemingly acquiesced to US demands. Although growth has slowed and certain industry sectors are feeling the pain, a global recession feels avoidable. Equity markets have even responded positively. However, this does not mean that it will be smooth sailing from here on. There are several risks, all with strong geopolitical angles, that bear watching. The global economy will be tested, and new flashpoints will emerge, but there is a reasonable chance that the world will find a way through these challenges and that globalization will reconfigure.

Reshaping global trade

It will take time, and there is considerable uncertainty surrounding how it will happen, but the world trade system can rewire. However, there are many bumps on the road ahead.

The global trade architecture is changing. Protectionism is on the rise, and many fear that international trade could be badly damaged. It will take time, and there is considerable uncertainty surrounding how it will happen, but the world trade system can rewire. However, there are many bumps on the road ahead.

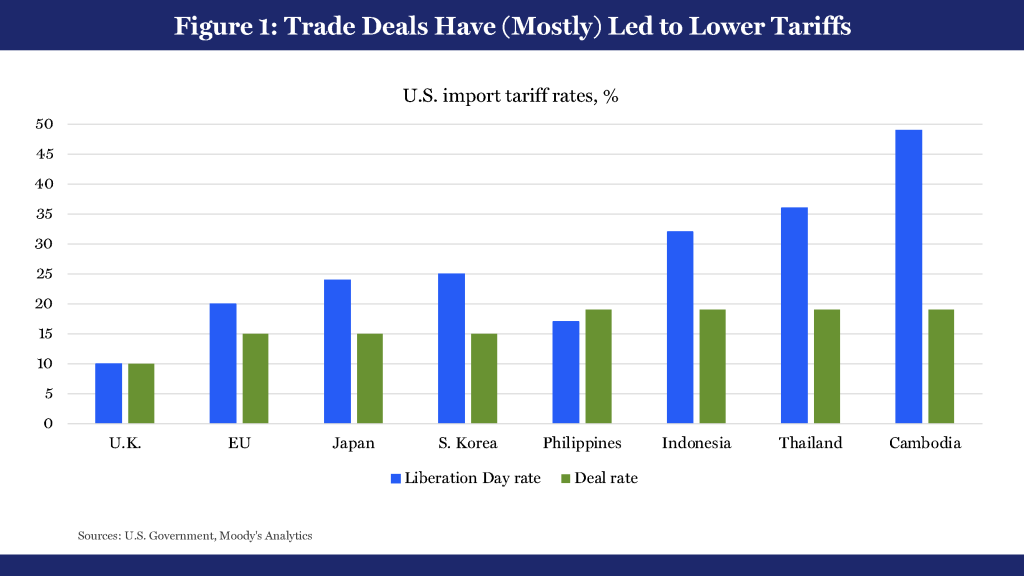

After a turbulent start to the year, the world is growing accustomed to tariffs on exports to the US. Some countries have even signed deals, agreeing to increase their imports in return for lower tariffs on exports. Presumably, countries are looking to make the best of a bad situation, as the alternative to not signing these deals would be even higher tariffs and a significant fall in exports. But tariffs come at a cost. Trade between countries allows comparative advantages to thrive, lowers prices, spurs innovation and increases consumer choice. Tariffs do the opposite.

Unsurprisingly, countries are trying to find alternatives to offset the decline in exports to the US. The European Union (EU) signed agreements with Mercosur (Southern Common Market) and Indonesia this year, and free-trade agreements (FTAs) are in the making with several Asian countries. China hopes to deepen its FTA with the ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) to include green tech and digital services. But changing the global trade architecture is like turning a supertanker—it takes time. If tariff barriers are too high to overcome and if substitute markets cannot be found, then manufacturing in several countries could go into secular decline. The US may achieve its objective of greater domestic reliance and a reversal of its trade deficit, but it could come at the expense of global manufacturing.

But between these bookends are numerous other scenarios—difficult to choose from—that as a group seem highly likely, ones whereby the supertanker does slowly turn.

There are a number of possible scenarios for global trade. The most optimistic, is one where tariffs are repealed, and we return to the old world order. This feels highly unlikely. In the bleakest scenario, countries resist and retaliate, precipitating a global recession. This risk remains uncomfortably high. But between these bookends are numerous other scenarios—difficult to choose from—that as a group seem highly likely, ones whereby the supertanker does slowly turn. Protectionism rises, but countries make a conscious attempt to trade more with each other. Different trading blocs could develop: one that is more aligned with the US, another that favors China and a third that seeks to remain neutral and pragmatic. World trade will not be as frictionless as before, and global growth will slow, but globalization will recover.

International capital and currencies

Rising US protectionism also affects international investment flows and demand for currencies. Given that the US has been a major global investor for decades and the US dollar is the world’s reserve currency, there is no clear way out. The uncertain outlook for international investment and the dissatisfaction with the US dollar are creating risks for the global economy.

As the US has signaled, it is seeking to invest less in other countries and wants to attract substantially more inward investment. One country that has already felt the brunt of this policy shift is China; investment flows have fallen off in recent years and are now at a virtual standstill. However, it is unclear whether the US will succeed in persuading other countries to invest there. More broadly, the US push to increase its manufacturing base and limit imports is also likely to negatively impact investments in other parts of the world. European manufacturing, already beleaguered, may go into a downward spiral, while a clampdown on Chinese transshipments may also spell trouble for investments into Southeast Asia. Offsetting these downside risks is the increased interest among other countries in signing trade deals with each other, which could also result in the development of supply chains in different parts of the world and drive investment.

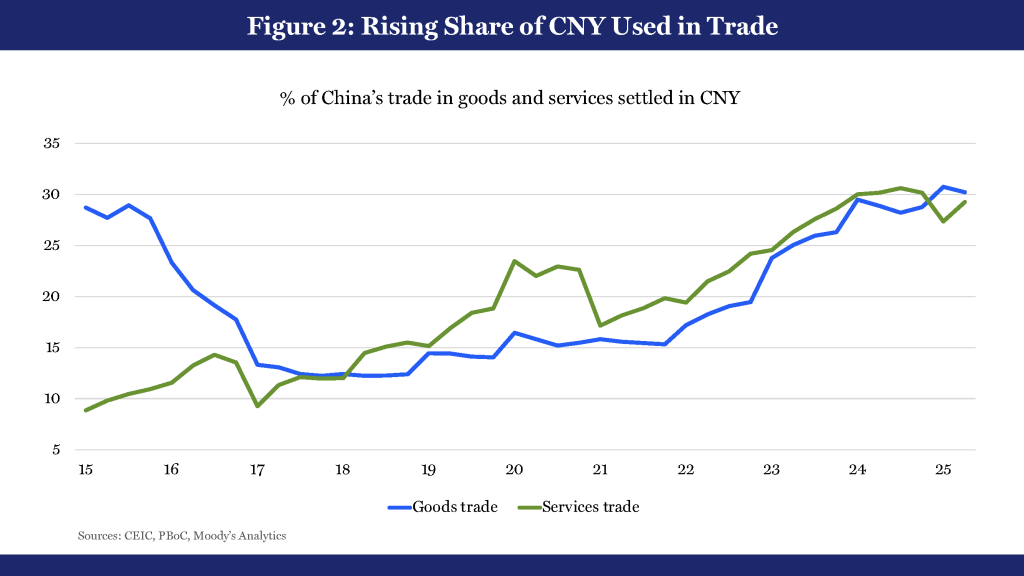

Countries will also seek to move away from the US dollar for international payments for both goods and commodities. The use of alternative currencies, such as the yuan, euro or even the currencies of Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) member states, will grow. However, there are limits to this expansion given the inability of the yuan or the euro to become a global reserve currency. Attempting to bypass the US dollar may also prompt sanctions that penalize those avoiding its use, especially if the intent is to evade the strictures of US policy. Finally, it is worth mentioning that dissatisfaction with fiat currencies could further speed the adoption of cryptocurrencies.

International investment could retrench sharply over the next couple of years. Countries may renege on their pledges to the US or find it impossible to fulfill them, and suitable opportunities in other parts of the world may not arise. Efforts to push out the US dollar may attract censure, leading to disorderly currency adjustments, while the greater use of cryptocurrencies could increase volatility in the financial system. At the extreme, a loss of trust could prompt large flows out of the US dollar. But these outcomes are not inevitable. Gradual structural changes in capital and currencies are more likely. While the equilibrium value of currencies and the direction of capital flows could change, countries will continue to invest in each other, and fiat money will prevail.

The technological frontier

Countries are jostling to be on the technological frontier, but concerns over a financial-market bubble and restrictions on the global supply of sensitive technologies and rare-earth elements (REEs) cloud the future.

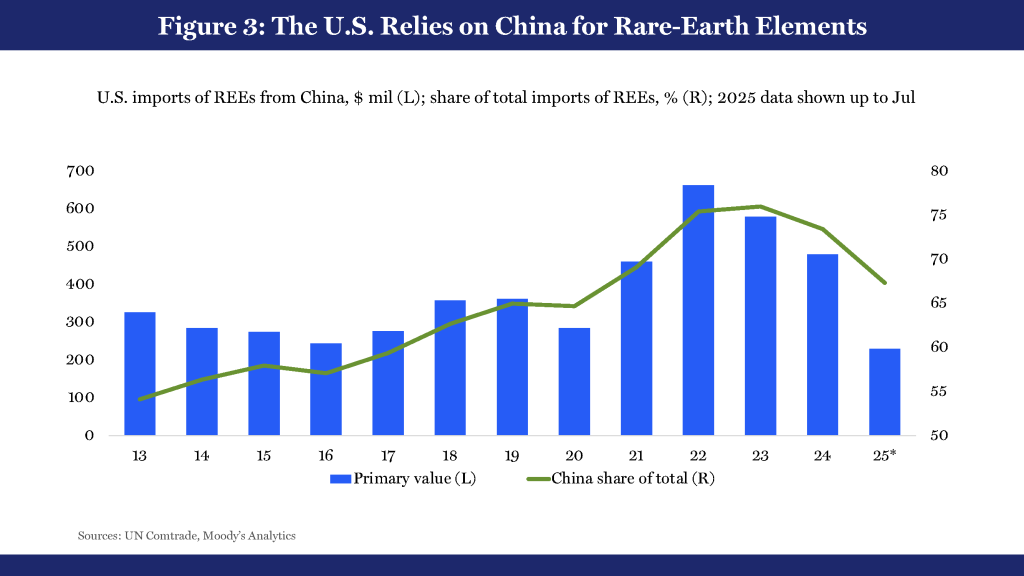

There is a race for artificial intelligence (AI) dominance through investment in “compute”—the processors, chips and storage needed for AI—and the energy required to power data centers. Given the high costs of entry, US mega firms enjoy a significant first-mover advantage, while some countries in Asia and the Middle East are seeking to gain a foothold through ambitious plans to build data centers, with innovative ideas such as “data embassies”. China, in turn, controls the REE supply and has a significant lead in refining technologies. China also leads in many of the “technologies of tomorrow”, from 5G-communications equipment to clean tech to drones. For many emerging markets, Chinese low-cost goods are a boon because they allow for much-needed upgrades to infrastructure and help with decarbonization.

However, concerns are growing about a possible AI bubble. The transformative potential of AI is unknown, and the pace of technological progress is uncertain. Societal risks also exist if AI leads to large-scale job losses, especially without regulation and fiscal policy moving at the correct pace. A steep market correction would be an acknowledgement of these unknowns, suggesting that the most promising engine of growth right now might have to continue in a lower gear. Such a correction could also spill over to other asset classes and result in broader financial instability.

Another area of concern is geopolitical. The US is keen to restrict China’s access to advanced chips and sensitive technologies, but China controls the global supply and refining of REEs, and the US relies heavily on these imports from China. The share of these materials in imports, by value, is small enough to be overlooked, yet their importance spans a broad range of manufacturing segments, from wind turbines to electric vehicles to defense equipment. China’s recent announcement of restrictions on exports of technologies related to REEs not only shows its willingness to escalate but also raises awareness of the profound disruption to the global economy that such an escalation would cause.

The risks are clearly weighted to the downside, but the future does not have to be dismal. Corrections to AI valuations do not have to lead to wider financial instability, and the US and China could yet find a solution that will keep trade, technological progress and global growth afloat.

Militarization and conflict

Advancing military capabilities is a geopolitical need with economic benefits. However, while the race to expand or maintain military capabilities presents an upside for growth, there is a distinct possibility that these gains will be elusive. The rise of geopolitical risk also raises concerns around conflicts and their escalation.

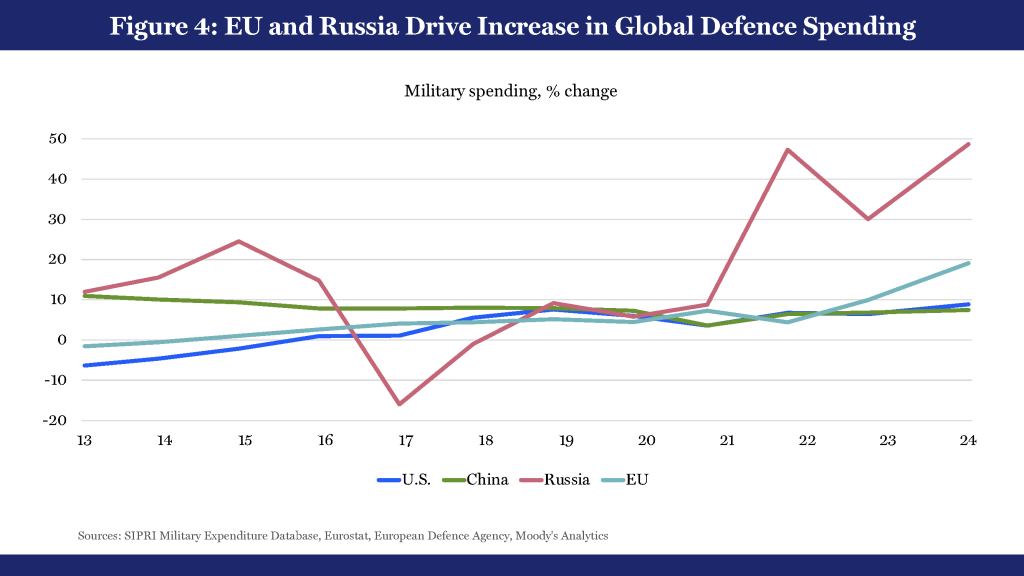

As a result of US insistence and its own vulnerability on its front with Russia, Europe has somewhat reluctantly acknowledged the need for greater defense spending. Meanwhile, the other big powers, China and the US, continue to advance their military capabilities, and nearly all of the nine nuclear powers are increasing their arsenals.

Defense spending is positive for growth and can benefit the global defense sector. But the results could also be disappointing. In terms of bang for the buck, defense spending has a lower impact on gross domestic product (GDP) than, say, spending on infrastructure, and it can also crowd out investments in other critical areas. Proponents of increased military capability point to the potential long-term spillover benefits that arise from pushing out the technological frontier, but such gains are hard to both predict and size. Burdened by cumbersome bureaucracy, a lack of fiscal space and even a perceived lack of urgency in some quarters, the European spending push might also underdeliver. The militarization drive by the big powers might also bump up against physical and geopolitical constraints, particularly the availability of and access to REEs. This could spill over into other risks.

As the last few years have shown, conflicts are on the rise. Russia’s recent drone incursions into Poland have displayed Europe’s vulnerabilities, while frictions between the US and China continue over the South China Sea and Taiwan. The recent peace deal in the Middle East is welcome news, but a future flare-up is still possible. Other countries have also attempted to settle scores this year, as demonstrated by the clashes between India and Pakistan, Cambodia and Vietnam. These have not had any macroeconomic consequences, but they have contributed to a sense of disquiet.

Global disarmament and de-escalation are events of the past. Equally, the other bookend, a damaging confrontation between the big powers, feels reasonably remote, leaving, once again, the “in-between” scenarios to contend with. These are scenarios in which increased military spending delivers some positive impetus to growth, but not as much as might be hoped for. Fractures in the geopolitical order continue, and tensions between big powers spill over to affect the economic system. Conflicts between smaller nations occur, but with limited economic consequences. The increased intertwining of geopolitical and economic interests impacts supply chains, especially in sectors seen as strategic, and adds to the frictions around globalization, without damaging it.

A brave new world

US dissatisfaction with globalization has changed the world this year. Other countries are trying to adjust to the new order while coping with their own internal discontent and economic issues. Added to this is ongoing climate change, which is slowly but surely impacting food and water security, migration and the economic structures of various countries. Going back to the world of yesterday seems impossible, but equally, the talk of collapse over the next few years feels overblown. The dust, when it settles, could form many different patterns, none of which need be deeply inimical to global growth. Until then, however, we will continue to feel twitchy.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Gaurav Ganguly is the Head of International Economics at Moody’s Analytics. He writes and speaks widely on Europe, Asia-Pacific, and the Middle East, and hosts the Global Economy Unwrapped podcast. He has taught at various universities in the UK and held several visiting academic positions. Dr. Ganguly holds a doctorate in Economics from the University of Oxford.

Dr. Gaurav Ganguly is the Head of International Economics at Moody’s Analytics. He writes and speaks widely on Europe, Asia-Pacific, and the Middle East, and hosts the Global Economy Unwrapped podcast. He has taught at various universities in the UK and held several visiting academic positions. Dr. Ganguly holds a doctorate in Economics from the University of Oxford.